Copper Market Signals a Global Economy in Transition

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

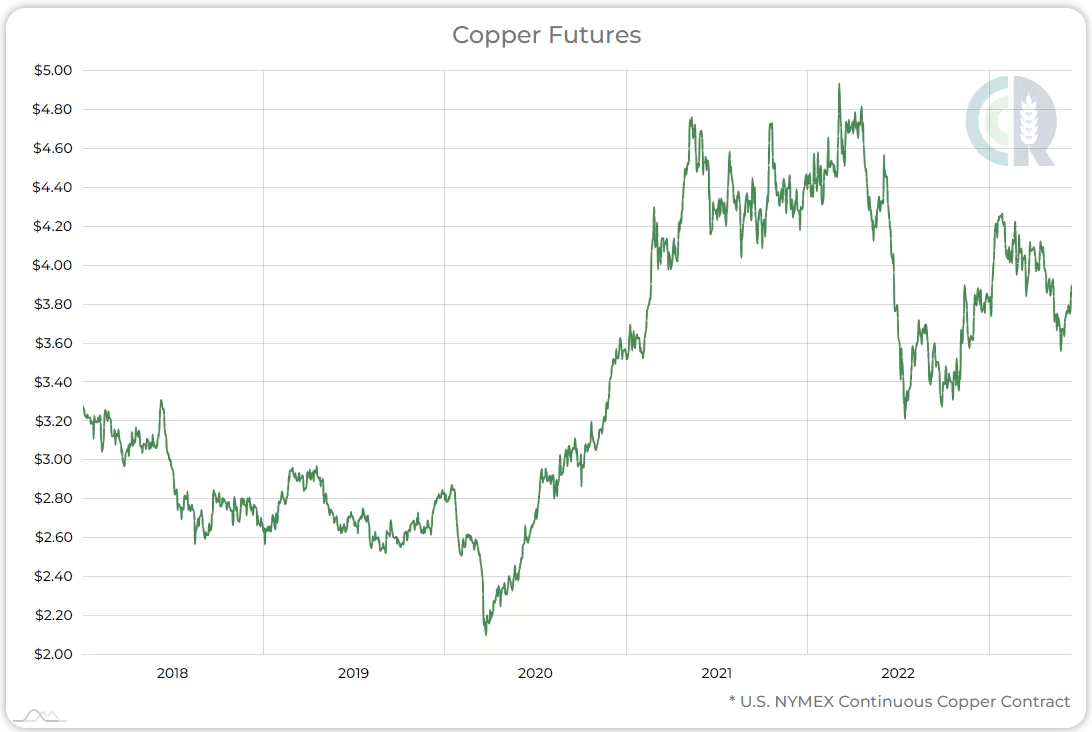

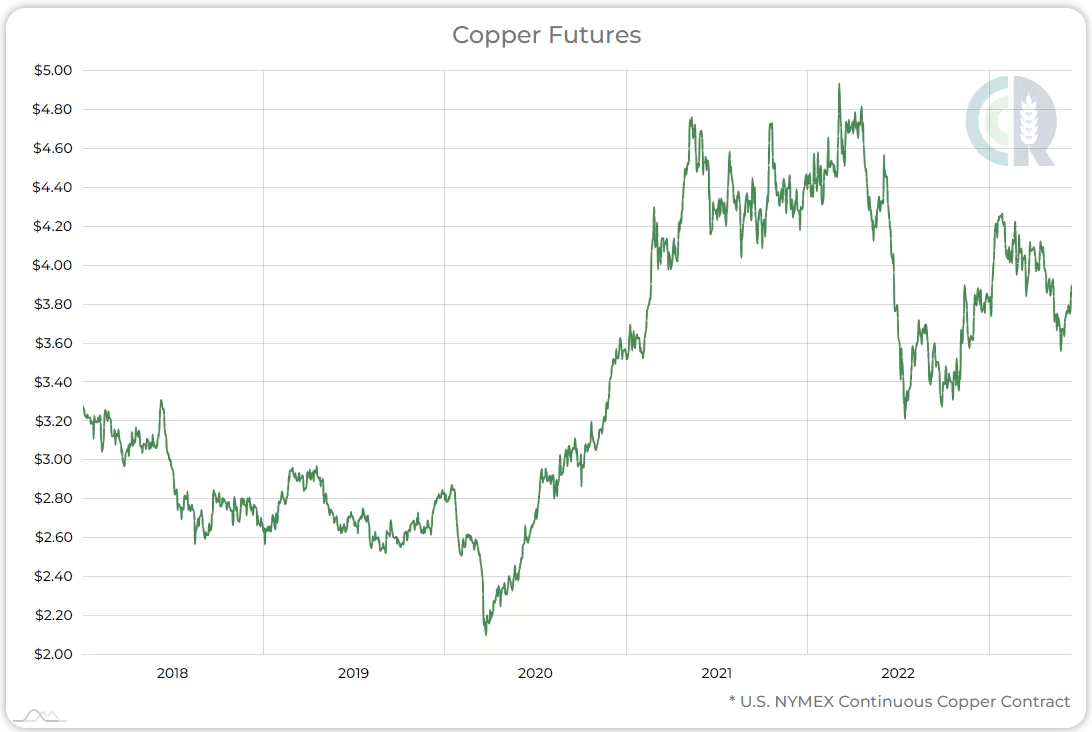

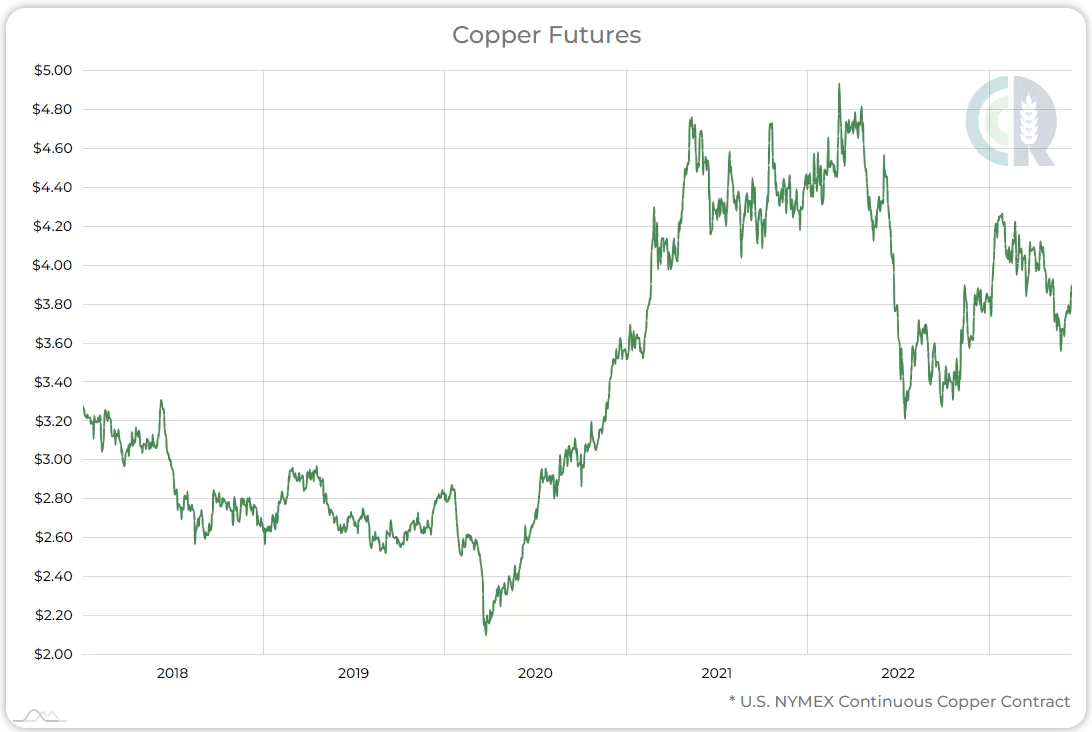

Copper was priced for perfection last year when it reached a high of nearly $5 per pound. In order to justify that price, the global economy would have had to be strong and, more importantly, China would need to continue to expand in the same manner that it had prior to 2018.

China is by far the world’s largest consumer of copper, accounting for more than half the global supply. The lion’s share of that goes toward infrastructure such as commercial buildings, homes, utilities, transportation, and machinery. Approximately 15% of China’s copper consumption goes into consumer durable goods, most of which are exported.

As with many other commodities, the price of copper reached a record high during the first half of 2022 before losing steam and giving back a significant portion of those gains. Much of the price action can be attributed to monetary inflation and economic uncertainty, but behind that we see the looming effects of a fundamental change to global commerce.

For the past 25 years, China has been the white knight for commodity prices. As they have grown from economic irrelevance to the world’s second largest economy, they have had an insatiable appetite for virtually all raw materials. Chief among them were metals like steel and copper, which were used to build out their vast manufacturing infrastructure.

Markets Have Grown Accustomed to China’s Relentless Economic Growth

Any nation that experiences rapid economic expansion must constantly reinvest in their own economy in order to sustain that growth. The faster the expansion, the greater the required investment. Growing economies tend to overbuild, and once that growth begins to taper off, they find themselves with excess capacity.

For years, China has been financing infrastructure projects at a rate never before seen during peacetime. They have sustained this model for so long that it can be difficult to remember a time when China was not the dominant force in the market for raw materials.

Investment analysts with two decades of experience have only ever known a world in which China’s economy is expanding at breakneck speed. Until they see conclusive evidence to the contrary, they will expect that paradigm to continue. The events of the past five years – beginning with former President Donald Trump’s trade war – are viewed as an aberration.

This is why many of our colleagues have been waiting with bated breath for China to reopen following their pandemic lockdowns. That would surely propel last year’s commodity inflation rally to new heights, or so they said.

Well, China’s zero-Covid policy has been officially over for six months now. Based on CCP data, China’s economy grew by 4.5% in Q1 of this year (2023), surpassing the expectation of 4% and showing a significant increase from last year’s Q4 growth of just 2.9%. Chinese exports have resumed, and their trade surplus has exceeded analyst forecasts.

Clearly, their manufacturing economy is back in full swing, but commodity prices have generally stagnated during that time. This could be a case of “buy the rumor, sell the news” for the agriculture and energy sectors, as most of the price gains were already baked in. Building materials are a different story, as there seems to have been a fundamental change in China’s approach to internal financing: China is reopening factories, not building new ones.

This is why we’ve seen a decent recovery in China’s consumption of crude oil, coal, and natural gas, but only tepid demand for iron, steel, copper, and lumber. It seems as though the multi-decade construction boom has ended.

Analysts continue to project that China will increase consumption of copper, but the actual figures keep falling short of expectations. According to the CCP’s General Administration of Customs, China imported 444,000 tons of unwrought copper and copper products in May 2023. This represents a 4.6% decline compared to May of last year, when the economy was still under tight Covid restrictions.

The Chinese economy is not the unstoppable force that many Westerners perceive it to be. It is still a force to be reckoned with, but it has its vulnerabilities. Their incredible rate of economic growth is unsustainable in the long run. Though few are predicting it now, in hindsight, the peak of China’s economy will seem obvious.

Is this the End for China?

No, a peak is not the same thing as a crash. China will continue to grow, just at a slower pace than we’re used to. They will continue manufacturing consumer products for the rest of the world, but they will do so in existing factories.

We see China continuing to grow at around 4% annually over the next few years, an enviable goal for most nations, but a far cry from their double-digit growth of the early 2000s. This more moderate rate of growth can be accomplished largely with their existing infrastructure. Some of China’s tapering off of infrastructure spending will be countered by other places like India, Africa, and Latin America expanding their own manufacturing capabilities, but that will not be enough to fully pick up the slack.

Supply of Copper is Increasing Steadily

JP Morgan projects global copper mine output to rise by 2.6% this year, which is on par with the growth rate over the past 10 years. They added a caveat that civil unrest in Peru, the world’s second largest producer behind Chile, could potentially curtail that growth.

Recycled copper accounts for about 30% of the global supply. This is an area ripe for growth as mining alone will have difficulty meeting future demand, and the process of recycling scrap copper requires only one-fifth of the energy used to refine copper ore. Additionally, the availability of high-quality scrap is sure to increase as the first generation of electric vehicles reach the end of their life cycles.

Copper Demand Growth Factors: Electric Vehicles and the Power Grid

Certainly, copper has more applications than just building materials. Its use in electric vehicle batteries, and electronics in general, will drive demand growth over the next decade. In addition to using copper in the batteries themselves (about 180 lbs. per vehicle), the required upgrade to electrical grids necessary to charge those vehicles will also require massive amounts of copper.

The transition to electric vehicles clearly has begun, but will take longer than anticipated. First and foremost, the sourcing of electricity must be addressed, as it makes little sense to switch to EVs if we’re still powering them with coal. Then the electrical grid in every country needs to expand greatly. Once the capacity to charge the batteries has been established, a shortage of rare minerals and precious metals will hinder their mass production. If they don’t have enough lithium or cobalt to build it, the copper becomes irrelevant. These hurdles are not insurmountable, but they will take some time to overcome.

S&P Global Market Intelligence projected demand for copper to double from 25 million metric tons last year to 50 million metric tons annually by 2035. Those figures are based on the assumption that China’s building construction sector will remain strong as the electric vehicle industry takes off. Such projections are typically optimistic about timing, and as a commodity trader, timing is everything.

Conclusion and Outlook

We agree with the consensus that demand for copper will grow significantly in coming years, but the near-term demand has been overstated. The forecasts depend largely on China continuing to build at a pace that now seems improbable.

As the battery revolution continues, there will come a point when copper will be in extremely high demand and short supply, but we don’t see that happening in 2023 – and probably not 2024 either.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Copper Market Signals a Global Economy in Transition

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform

Copper was priced for perfection last year when it reached a high of nearly $5 per pound. In order to justify that price, the global economy would have had to be strong and, more importantly, China would need to continue to expand in the same manner that it had prior to 2018.

China is by far the world’s largest consumer of copper, accounting for more than half the global supply. The lion’s share of that goes toward infrastructure such as commercial buildings, homes, utilities, transportation, and machinery. Approximately 15% of China’s copper consumption goes into consumer durable goods, most of which are exported.

As with many other commodities, the price of copper reached a record high during the first half of 2022 before losing steam and giving back a significant portion of those gains. Much of the price action can be attributed to monetary inflation and economic uncertainty, but behind that we see the looming effects of a fundamental change to global commerce.

For the past 25 years, China has been the white knight for commodity prices. As they have grown from economic irrelevance to the world’s second largest economy, they have had an insatiable appetite for virtually all raw materials. Chief among them were metals like steel and copper, which were used to build out their vast manufacturing infrastructure.

Markets Have Grown Accustomed to China’s Relentless Economic Growth

Any nation that experiences rapid economic expansion must constantly reinvest in their own economy in order to sustain that growth. The faster the expansion, the greater the required investment. Growing economies tend to overbuild, and once that growth begins to taper off, they find themselves with excess capacity.

For years, China has been financing infrastructure projects at a rate never before seen during peacetime. They have sustained this model for so long that it can be difficult to remember a time when China was not the dominant force in the market for raw materials.

Investment analysts with two decades of experience have only ever known a world in which China’s economy is expanding at breakneck speed. Until they see conclusive evidence to the contrary, they will expect that paradigm to continue. The events of the past five years – beginning with former President Donald Trump’s trade war – are viewed as an aberration.

This is why many of our colleagues have been waiting with bated breath for China to reopen following their pandemic lockdowns. That would surely propel last year’s commodity inflation rally to new heights, or so they said.

Well, China’s zero-Covid policy has been officially over for six months now. Based on CCP data, China’s economy grew by 4.5% in Q1 of this year (2023), surpassing the expectation of 4% and showing a significant increase from last year’s Q4 growth of just 2.9%. Chinese exports have resumed, and their trade surplus has exceeded analyst forecasts.

Clearly, their manufacturing economy is back in full swing, but commodity prices have generally stagnated during that time. This could be a case of “buy the rumor, sell the news” for the agriculture and energy sectors, as most of the price gains were already baked in. Building materials are a different story, as there seems to have been a fundamental change in China’s approach to internal financing: China is reopening factories, not building new ones.

This is why we’ve seen a decent recovery in China’s consumption of crude oil, coal, and natural gas, but only tepid demand for iron, steel, copper, and lumber. It seems as though the multi-decade construction boom has ended.

Analysts continue to project that China will increase consumption of copper, but the actual figures keep falling short of expectations. According to the CCP’s General Administration of Customs, China imported 444,000 tons of unwrought copper and copper products in May 2023. This represents a 4.6% decline compared to May of last year, when the economy was still under tight Covid restrictions.

The Chinese economy is not the unstoppable force that many Westerners perceive it to be. It is still a force to be reckoned with, but it has its vulnerabilities. Their incredible rate of economic growth is unsustainable in the long run. Though few are predicting it now, in hindsight, the peak of China’s economy will seem obvious.

Is this the End for China?

No, a peak is not the same thing as a crash. China will continue to grow, just at a slower pace than we’re used to. They will continue manufacturing consumer products for the rest of the world, but they will do so in existing factories.

We see China continuing to grow at around 4% annually over the next few years, an enviable goal for most nations, but a far cry from their double-digit growth of the early 2000s. This more moderate rate of growth can be accomplished largely with their existing infrastructure. Some of China’s tapering off of infrastructure spending will be countered by other places like India, Africa, and Latin America expanding their own manufacturing capabilities, but that will not be enough to fully pick up the slack.

Supply of Copper is Increasing Steadily

JP Morgan projects global copper mine output to rise by 2.6% this year, which is on par with the growth rate over the past 10 years. They added a caveat that civil unrest in Peru, the world’s second largest producer behind Chile, could potentially curtail that growth.

Recycled copper accounts for about 30% of the global supply. This is an area ripe for growth as mining alone will have difficulty meeting future demand, and the process of recycling scrap copper requires only one-fifth of the energy used to refine copper ore. Additionally, the availability of high-quality scrap is sure to increase as the first generation of electric vehicles reach the end of their life cycles.

Copper Demand Growth Factors: Electric Vehicles and the Power Grid

Certainly, copper has more applications than just building materials. Its use in electric vehicle batteries, and electronics in general, will drive demand growth over the next decade. In addition to using copper in the batteries themselves (about 180 lbs. per vehicle), the required upgrade to electrical grids necessary to charge those vehicles will also require massive amounts of copper.

The transition to electric vehicles clearly has begun, but will take longer than anticipated. First and foremost, the sourcing of electricity must be addressed, as it makes little sense to switch to EVs if we’re still powering them with coal. Then the electrical grid in every country needs to expand greatly. Once the capacity to charge the batteries has been established, a shortage of rare minerals and precious metals will hinder their mass production. If they don’t have enough lithium or cobalt to build it, the copper becomes irrelevant. These hurdles are not insurmountable, but they will take some time to overcome.

S&P Global Market Intelligence projected demand for copper to double from 25 million metric tons last year to 50 million metric tons annually by 2035. Those figures are based on the assumption that China’s building construction sector will remain strong as the electric vehicle industry takes off. Such projections are typically optimistic about timing, and as a commodity trader, timing is everything.

Conclusion and Outlook

We agree with the consensus that demand for copper will grow significantly in coming years, but the near-term demand has been overstated. The forecasts depend largely on China continuing to build at a pace that now seems improbable.

As the battery revolution continues, there will come a point when copper will be in extremely high demand and short supply, but we don’t see that happening in 2023 – and probably not 2024 either.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Copper Market Signals a Global Economy in Transition

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform

Copper was priced for perfection last year when it reached a high of nearly $5 per pound. In order to justify that price, the global economy would have had to be strong and, more importantly, China would need to continue to expand in the same manner that it had prior to 2018.

China is by far the world’s largest consumer of copper, accounting for more than half the global supply. The lion’s share of that goes toward infrastructure such as commercial buildings, homes, utilities, transportation, and machinery. Approximately 15% of China’s copper consumption goes into consumer durable goods, most of which are exported.

As with many other commodities, the price of copper reached a record high during the first half of 2022 before losing steam and giving back a significant portion of those gains. Much of the price action can be attributed to monetary inflation and economic uncertainty, but behind that we see the looming effects of a fundamental change to global commerce.

For the past 25 years, China has been the white knight for commodity prices. As they have grown from economic irrelevance to the world’s second largest economy, they have had an insatiable appetite for virtually all raw materials. Chief among them were metals like steel and copper, which were used to build out their vast manufacturing infrastructure.

Markets Have Grown Accustomed to China’s Relentless Economic Growth

Any nation that experiences rapid economic expansion must constantly reinvest in their own economy in order to sustain that growth. The faster the expansion, the greater the required investment. Growing economies tend to overbuild, and once that growth begins to taper off, they find themselves with excess capacity.

For years, China has been financing infrastructure projects at a rate never before seen during peacetime. They have sustained this model for so long that it can be difficult to remember a time when China was not the dominant force in the market for raw materials.

Investment analysts with two decades of experience have only ever known a world in which China’s economy is expanding at breakneck speed. Until they see conclusive evidence to the contrary, they will expect that paradigm to continue. The events of the past five years – beginning with former President Donald Trump’s trade war – are viewed as an aberration.

This is why many of our colleagues have been waiting with bated breath for China to reopen following their pandemic lockdowns. That would surely propel last year’s commodity inflation rally to new heights, or so they said.

Well, China’s zero-Covid policy has been officially over for six months now. Based on CCP data, China’s economy grew by 4.5% in Q1 of this year (2023), surpassing the expectation of 4% and showing a significant increase from last year’s Q4 growth of just 2.9%. Chinese exports have resumed, and their trade surplus has exceeded analyst forecasts.

Clearly, their manufacturing economy is back in full swing, but commodity prices have generally stagnated during that time. This could be a case of “buy the rumor, sell the news” for the agriculture and energy sectors, as most of the price gains were already baked in. Building materials are a different story, as there seems to have been a fundamental change in China’s approach to internal financing: China is reopening factories, not building new ones.

This is why we’ve seen a decent recovery in China’s consumption of crude oil, coal, and natural gas, but only tepid demand for iron, steel, copper, and lumber. It seems as though the multi-decade construction boom has ended.

Analysts continue to project that China will increase consumption of copper, but the actual figures keep falling short of expectations. According to the CCP’s General Administration of Customs, China imported 444,000 tons of unwrought copper and copper products in May 2023. This represents a 4.6% decline compared to May of last year, when the economy was still under tight Covid restrictions.

The Chinese economy is not the unstoppable force that many Westerners perceive it to be. It is still a force to be reckoned with, but it has its vulnerabilities. Their incredible rate of economic growth is unsustainable in the long run. Though few are predicting it now, in hindsight, the peak of China’s economy will seem obvious.

Is this the End for China?

No, a peak is not the same thing as a crash. China will continue to grow, just at a slower pace than we’re used to. They will continue manufacturing consumer products for the rest of the world, but they will do so in existing factories.

We see China continuing to grow at around 4% annually over the next few years, an enviable goal for most nations, but a far cry from their double-digit growth of the early 2000s. This more moderate rate of growth can be accomplished largely with their existing infrastructure. Some of China’s tapering off of infrastructure spending will be countered by other places like India, Africa, and Latin America expanding their own manufacturing capabilities, but that will not be enough to fully pick up the slack.

Supply of Copper is Increasing Steadily

JP Morgan projects global copper mine output to rise by 2.6% this year, which is on par with the growth rate over the past 10 years. They added a caveat that civil unrest in Peru, the world’s second largest producer behind Chile, could potentially curtail that growth.

Recycled copper accounts for about 30% of the global supply. This is an area ripe for growth as mining alone will have difficulty meeting future demand, and the process of recycling scrap copper requires only one-fifth of the energy used to refine copper ore. Additionally, the availability of high-quality scrap is sure to increase as the first generation of electric vehicles reach the end of their life cycles.

Copper Demand Growth Factors: Electric Vehicles and the Power Grid

Certainly, copper has more applications than just building materials. Its use in electric vehicle batteries, and electronics in general, will drive demand growth over the next decade. In addition to using copper in the batteries themselves (about 180 lbs. per vehicle), the required upgrade to electrical grids necessary to charge those vehicles will also require massive amounts of copper.

The transition to electric vehicles clearly has begun, but will take longer than anticipated. First and foremost, the sourcing of electricity must be addressed, as it makes little sense to switch to EVs if we’re still powering them with coal. Then the electrical grid in every country needs to expand greatly. Once the capacity to charge the batteries has been established, a shortage of rare minerals and precious metals will hinder their mass production. If they don’t have enough lithium or cobalt to build it, the copper becomes irrelevant. These hurdles are not insurmountable, but they will take some time to overcome.

S&P Global Market Intelligence projected demand for copper to double from 25 million metric tons last year to 50 million metric tons annually by 2035. Those figures are based on the assumption that China’s building construction sector will remain strong as the electric vehicle industry takes off. Such projections are typically optimistic about timing, and as a commodity trader, timing is everything.

Conclusion and Outlook

We agree with the consensus that demand for copper will grow significantly in coming years, but the near-term demand has been overstated. The forecasts depend largely on China continuing to build at a pace that now seems improbable.

As the battery revolution continues, there will come a point when copper will be in extremely high demand and short supply, but we don’t see that happening in 2023 – and probably not 2024 either.