Brazilian Coffee Poised to Cause Market Jitters

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

- Dwindling stockpiles and seasonal weather patterns will likely lead to increased coffee price volatility in the coming weeks and months.

- As demand has grown steadily over the past three years, supply has experienced several hiccups.

- November is a pivotal time for next year’s Arabica crop.

- What does the coffee market have in store for us in 2024, and what potential red flags should you keep an eye on?

After three years of La Niña, the climate pattern shifted to El Niño earlier this year, bringing warmer weather to Colombia and northern Brazil. This reduces the chances of frost occurring in that region, but increases the likelihood of a drought.

Reporting indicates Brazilian coffee trees are looking quite healthy after receiving favorable weather since the transition took place. Those reports should be taken with a grain of salt, however, as they are typically based on visits to large and centrally located plantations in the State of Minas Gerais.

Smaller, more remote coffee growers may have a different experience. The low market price for coffee, relative strength of the Brazilian Real, and inflated cost of labor, fuel, fertilizer, and pesticides are forcing poorer plantations to cut costs. We’ve heard anecdotal reports of farmers neglecting their trees or switching to lower cost crops like lettuce or bananas.

Production Growth Trajectory For Brazilian Coffee

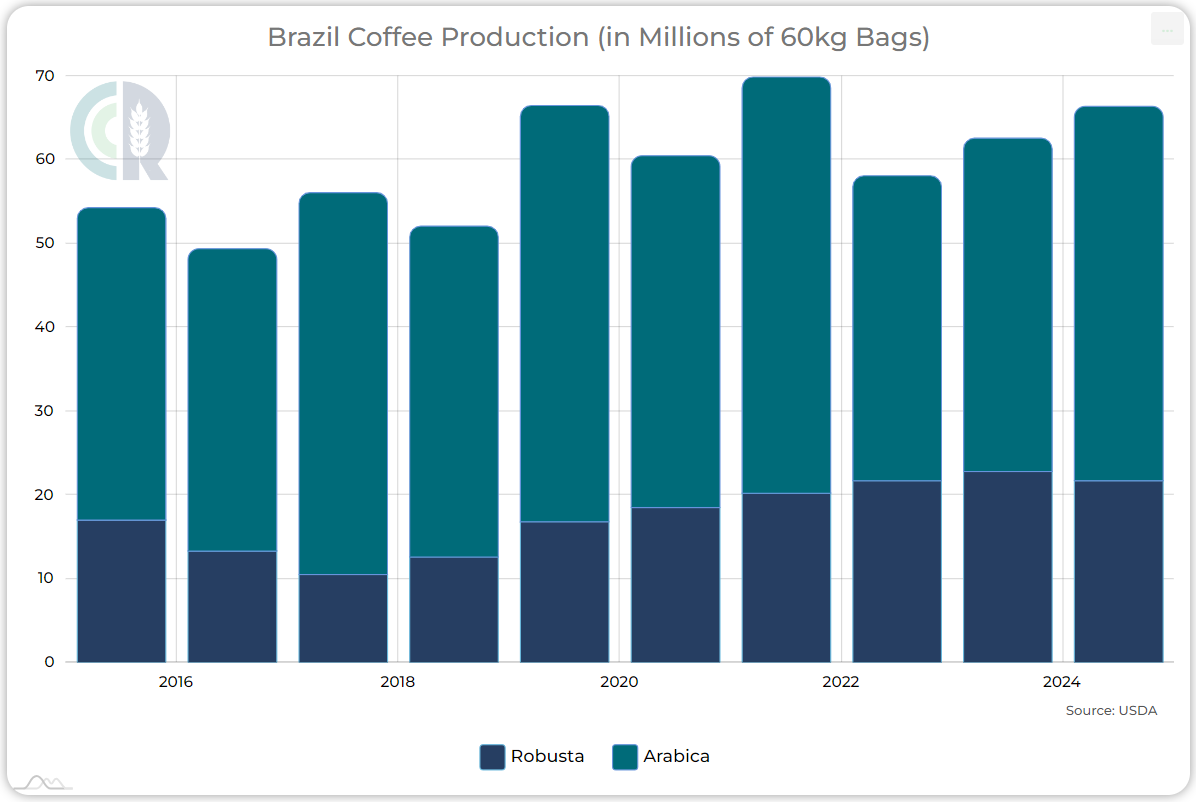

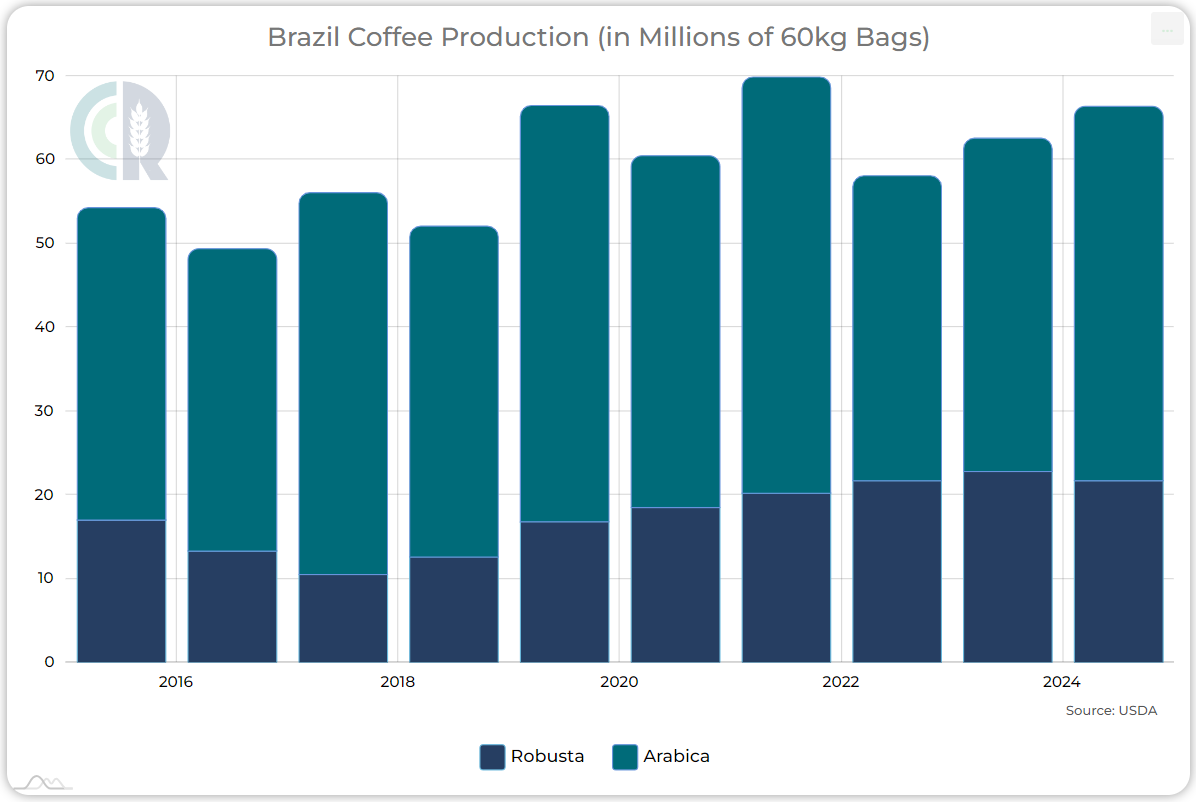

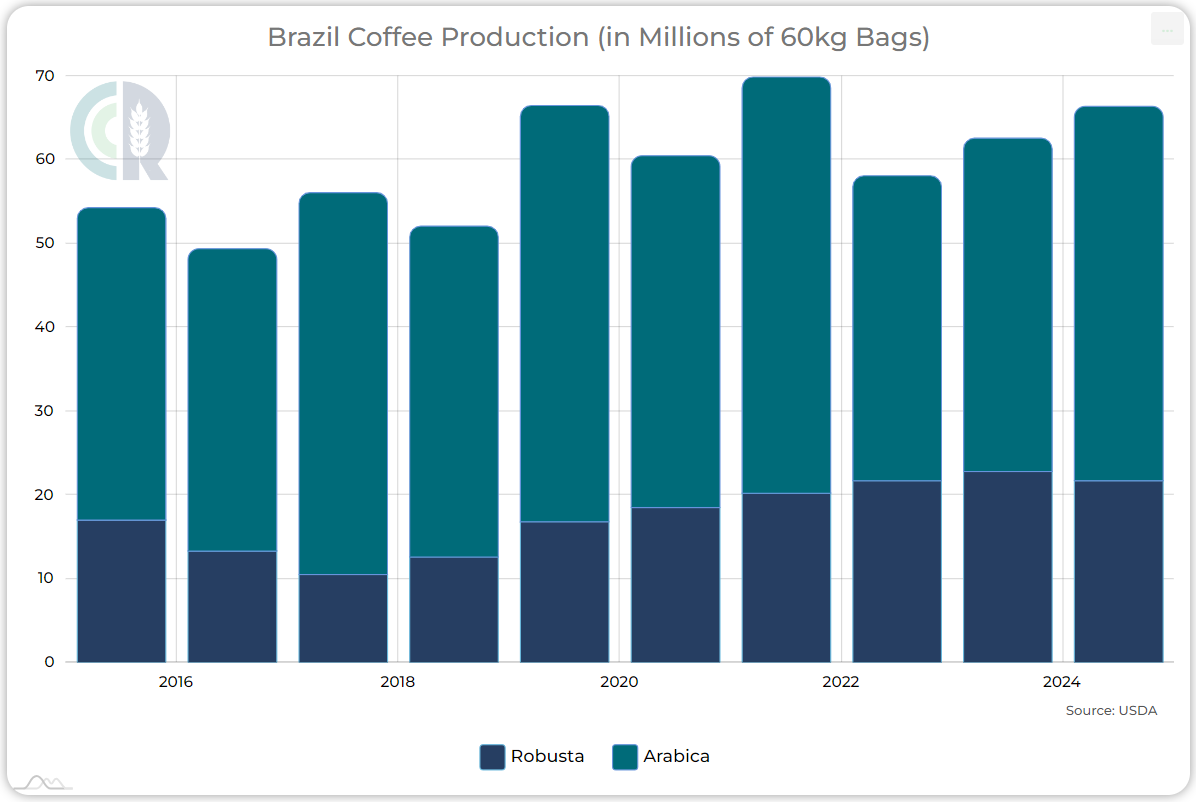

The 2022/23 coffee crop was slated to be an “on” year in the biennial Arabica cycle, meaning production was expected to increase over the previous year. While it did surpass the off cycle year of 2021/22, it wasn’t by much. Ordinarily – looking beyond the alternating year pattern – we would also expect to see a long-term upward trend line in total coffee production, but that has not been the case of late.

Coffee traders know all about the biennial cycle for Arabica trees, wherein they produce greater and lesser quantities of cherries in alternating years. This can be seen in the Brazilian production figures going up and down.

The 2022/23 production year failed to surpass the previous two “on” years, leading some coffee horticulturalists to speculate earlier this year that the cycle has been disrupted and ultimately may switch. Essentially, the hypothesis is that we had two down years in a row, so now we are due for an up year and the cycle has been reset.

Over the course of the past nine months, Arabica production forecasts for next year (2023/24) have been raised substantially as the biennial disruption hypothesis gained support. While Arabica production estimates have increased, Robusta estimates have been slightly lowered due to suboptimal growing conditions in Vietnam and Indonesia. The net result is expected to be a small increase in supply.

After three consecutive years in which coffee consumption exceeded production, warehouse stockpiles are hovering around a 23-year low. Consumption continues to grow, so even assuming that this will be an “on” year for Arabica, global coffee production is forecast to be right on par with consumption at about 174 million bags (each bag contains 60 kg of green coffee beans).

With production just barely keeping pace with consumption, the expectation is for essentially no change in ending stocks next year. In the best case scenario, there will be a small uptick in stockpiles, but they will remain critically low (between 31-34 million bags). Based on these forecasts, we can expect the worldwide coffee market to remain tight next year. But it’s early in the season, and forecasts could change.

The Flowering Season for Brazilian Coffee

There are two critical weather patterns that coffee growers must get through each year. The first is frost season during the Southern Hemisphere’s winter which we discussed in our March coffee article. In spite of some early concerns, they made it through that without much trouble this year.

The second is the flowering season during springtime (October and November), when Minas Gerais and other coffee growing regions receive most of their rain. This is always an important season for the following year’s coffee crop. If the rain doesn’t show up on time, coffee prices typically begin to rally.

Often, these rallies turn out to be selling opportunities because the drought fears were overhyped. This year, however, we would proceed with extreme caution. There is greater than usual upside price exposure going into next year due to the continuing tightness of supply, uncertainty regarding the biennial growth cycle, and ever-increasing global demand. If the 2023/24 production falls a bit short of expectations, there will be a worldwide coffee shortage.

Conclusion and Outlook

The next six weeks will be a pivotal time for next year’s crop. In all likelihood, there will be adequate rain and we’ll see stronger production next year and coffee prices will moderate. If, however, we have a down year in production- whether it be due to the biennial cycle reverting, lack of precipitation or lack of investment by plantations, it would lead to an unprecedented fourth consecutive drawdown in stockpiles and the shortage could be severe.

It’s too early to predict how next year’s harvest will turn out. With all the uncertainty hanging over this market, we see significant risk to the upside and therefore have a mildly bullish stance at this time.

We’ll have a much clearer picture by the end of November, after it either rains or doesn’t, and will be issuing our 2024 price forecast by the end of the year.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Brazilian Coffee Poised to Cause Market Jitters

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform

- Dwindling stockpiles and seasonal weather patterns will likely lead to increased coffee price volatility in the coming weeks and months.

- As demand has grown steadily over the past three years, supply has experienced several hiccups.

- November is a pivotal time for next year’s Arabica crop.

- What does the coffee market have in store for us in 2024, and what potential red flags should you keep an eye on?

After three years of La Niña, the climate pattern shifted to El Niño earlier this year, bringing warmer weather to Colombia and northern Brazil. This reduces the chances of frost occurring in that region, but increases the likelihood of a drought.

Reporting indicates Brazilian coffee trees are looking quite healthy after receiving favorable weather since the transition took place. Those reports should be taken with a grain of salt, however, as they are typically based on visits to large and centrally located plantations in the State of Minas Gerais.

Smaller, more remote coffee growers may have a different experience. The low market price for coffee, relative strength of the Brazilian Real, and inflated cost of labor, fuel, fertilizer, and pesticides are forcing poorer plantations to cut costs. We’ve heard anecdotal reports of farmers neglecting their trees or switching to lower cost crops like lettuce or bananas.

Production Growth Trajectory For Brazilian Coffee

The 2022/23 coffee crop was slated to be an “on” year in the biennial Arabica cycle, meaning production was expected to increase over the previous year. While it did surpass the off cycle year of 2021/22, it wasn’t by much. Ordinarily – looking beyond the alternating year pattern – we would also expect to see a long-term upward trend line in total coffee production, but that has not been the case of late.

Coffee traders know all about the biennial cycle for Arabica trees, wherein they produce greater and lesser quantities of cherries in alternating years. This can be seen in the Brazilian production figures going up and down.

The 2022/23 production year failed to surpass the previous two “on” years, leading some coffee horticulturalists to speculate earlier this year that the cycle has been disrupted and ultimately may switch. Essentially, the hypothesis is that we had two down years in a row, so now we are due for an up year and the cycle has been reset.

Over the course of the past nine months, Arabica production forecasts for next year (2023/24) have been raised substantially as the biennial disruption hypothesis gained support. While Arabica production estimates have increased, Robusta estimates have been slightly lowered due to suboptimal growing conditions in Vietnam and Indonesia. The net result is expected to be a small increase in supply.

After three consecutive years in which coffee consumption exceeded production, warehouse stockpiles are hovering around a 23-year low. Consumption continues to grow, so even assuming that this will be an “on” year for Arabica, global coffee production is forecast to be right on par with consumption at about 174 million bags (each bag contains 60 kg of green coffee beans).

With production just barely keeping pace with consumption, the expectation is for essentially no change in ending stocks next year. In the best case scenario, there will be a small uptick in stockpiles, but they will remain critically low (between 31-34 million bags). Based on these forecasts, we can expect the worldwide coffee market to remain tight next year. But it’s early in the season, and forecasts could change.

The Flowering Season for Brazilian Coffee

There are two critical weather patterns that coffee growers must get through each year. The first is frost season during the Southern Hemisphere’s winter which we discussed in our March coffee article. In spite of some early concerns, they made it through that without much trouble this year.

The second is the flowering season during springtime (October and November), when Minas Gerais and other coffee growing regions receive most of their rain. This is always an important season for the following year’s coffee crop. If the rain doesn’t show up on time, coffee prices typically begin to rally.

Often, these rallies turn out to be selling opportunities because the drought fears were overhyped. This year, however, we would proceed with extreme caution. There is greater than usual upside price exposure going into next year due to the continuing tightness of supply, uncertainty regarding the biennial growth cycle, and ever-increasing global demand. If the 2023/24 production falls a bit short of expectations, there will be a worldwide coffee shortage.

Conclusion and Outlook

The next six weeks will be a pivotal time for next year’s crop. In all likelihood, there will be adequate rain and we’ll see stronger production next year and coffee prices will moderate. If, however, we have a down year in production- whether it be due to the biennial cycle reverting, lack of precipitation or lack of investment by plantations, it would lead to an unprecedented fourth consecutive drawdown in stockpiles and the shortage could be severe.

It’s too early to predict how next year’s harvest will turn out. With all the uncertainty hanging over this market, we see significant risk to the upside and therefore have a mildly bullish stance at this time.

We’ll have a much clearer picture by the end of November, after it either rains or doesn’t, and will be issuing our 2024 price forecast by the end of the year.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Brazilian Coffee Poised to Cause Market Jitters

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform

- Dwindling stockpiles and seasonal weather patterns will likely lead to increased coffee price volatility in the coming weeks and months.

- As demand has grown steadily over the past three years, supply has experienced several hiccups.

- November is a pivotal time for next year’s Arabica crop.

- What does the coffee market have in store for us in 2024, and what potential red flags should you keep an eye on?

After three years of La Niña, the climate pattern shifted to El Niño earlier this year, bringing warmer weather to Colombia and northern Brazil. This reduces the chances of frost occurring in that region, but increases the likelihood of a drought.

Reporting indicates Brazilian coffee trees are looking quite healthy after receiving favorable weather since the transition took place. Those reports should be taken with a grain of salt, however, as they are typically based on visits to large and centrally located plantations in the State of Minas Gerais.

Smaller, more remote coffee growers may have a different experience. The low market price for coffee, relative strength of the Brazilian Real, and inflated cost of labor, fuel, fertilizer, and pesticides are forcing poorer plantations to cut costs. We’ve heard anecdotal reports of farmers neglecting their trees or switching to lower cost crops like lettuce or bananas.

Production Growth Trajectory For Brazilian Coffee

The 2022/23 coffee crop was slated to be an “on” year in the biennial Arabica cycle, meaning production was expected to increase over the previous year. While it did surpass the off cycle year of 2021/22, it wasn’t by much. Ordinarily – looking beyond the alternating year pattern – we would also expect to see a long-term upward trend line in total coffee production, but that has not been the case of late.

Coffee traders know all about the biennial cycle for Arabica trees, wherein they produce greater and lesser quantities of cherries in alternating years. This can be seen in the Brazilian production figures going up and down.

The 2022/23 production year failed to surpass the previous two “on” years, leading some coffee horticulturalists to speculate earlier this year that the cycle has been disrupted and ultimately may switch. Essentially, the hypothesis is that we had two down years in a row, so now we are due for an up year and the cycle has been reset.

Over the course of the past nine months, Arabica production forecasts for next year (2023/24) have been raised substantially as the biennial disruption hypothesis gained support. While Arabica production estimates have increased, Robusta estimates have been slightly lowered due to suboptimal growing conditions in Vietnam and Indonesia. The net result is expected to be a small increase in supply.

After three consecutive years in which coffee consumption exceeded production, warehouse stockpiles are hovering around a 23-year low. Consumption continues to grow, so even assuming that this will be an “on” year for Arabica, global coffee production is forecast to be right on par with consumption at about 174 million bags (each bag contains 60 kg of green coffee beans).

With production just barely keeping pace with consumption, the expectation is for essentially no change in ending stocks next year. In the best case scenario, there will be a small uptick in stockpiles, but they will remain critically low (between 31-34 million bags). Based on these forecasts, we can expect the worldwide coffee market to remain tight next year. But it’s early in the season, and forecasts could change.

The Flowering Season for Brazilian Coffee

There are two critical weather patterns that coffee growers must get through each year. The first is frost season during the Southern Hemisphere’s winter which we discussed in our March coffee article. In spite of some early concerns, they made it through that without much trouble this year.

The second is the flowering season during springtime (October and November), when Minas Gerais and other coffee growing regions receive most of their rain. This is always an important season for the following year’s coffee crop. If the rain doesn’t show up on time, coffee prices typically begin to rally.

Often, these rallies turn out to be selling opportunities because the drought fears were overhyped. This year, however, we would proceed with extreme caution. There is greater than usual upside price exposure going into next year due to the continuing tightness of supply, uncertainty regarding the biennial growth cycle, and ever-increasing global demand. If the 2023/24 production falls a bit short of expectations, there will be a worldwide coffee shortage.

Conclusion and Outlook

The next six weeks will be a pivotal time for next year’s crop. In all likelihood, there will be adequate rain and we’ll see stronger production next year and coffee prices will moderate. If, however, we have a down year in production- whether it be due to the biennial cycle reverting, lack of precipitation or lack of investment by plantations, it would lead to an unprecedented fourth consecutive drawdown in stockpiles and the shortage could be severe.

It’s too early to predict how next year’s harvest will turn out. With all the uncertainty hanging over this market, we see significant risk to the upside and therefore have a mildly bullish stance at this time.

We’ll have a much clearer picture by the end of November, after it either rains or doesn’t, and will be issuing our 2024 price forecast by the end of the year.