Cracking the Gasoline Market

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

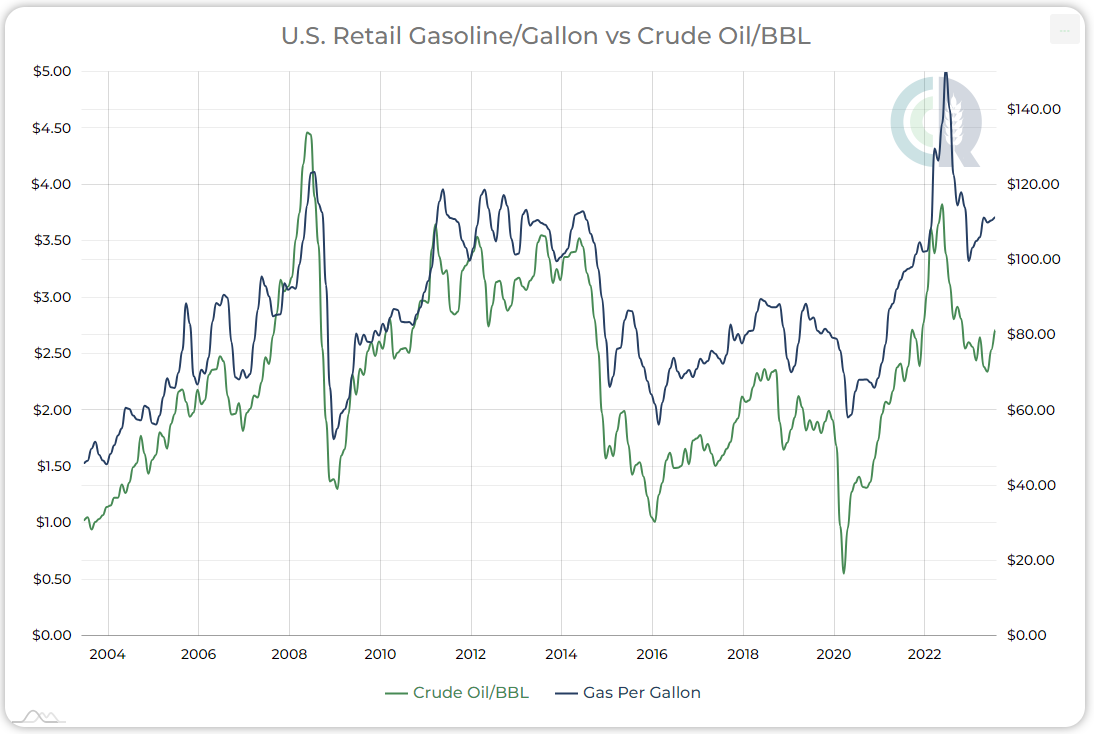

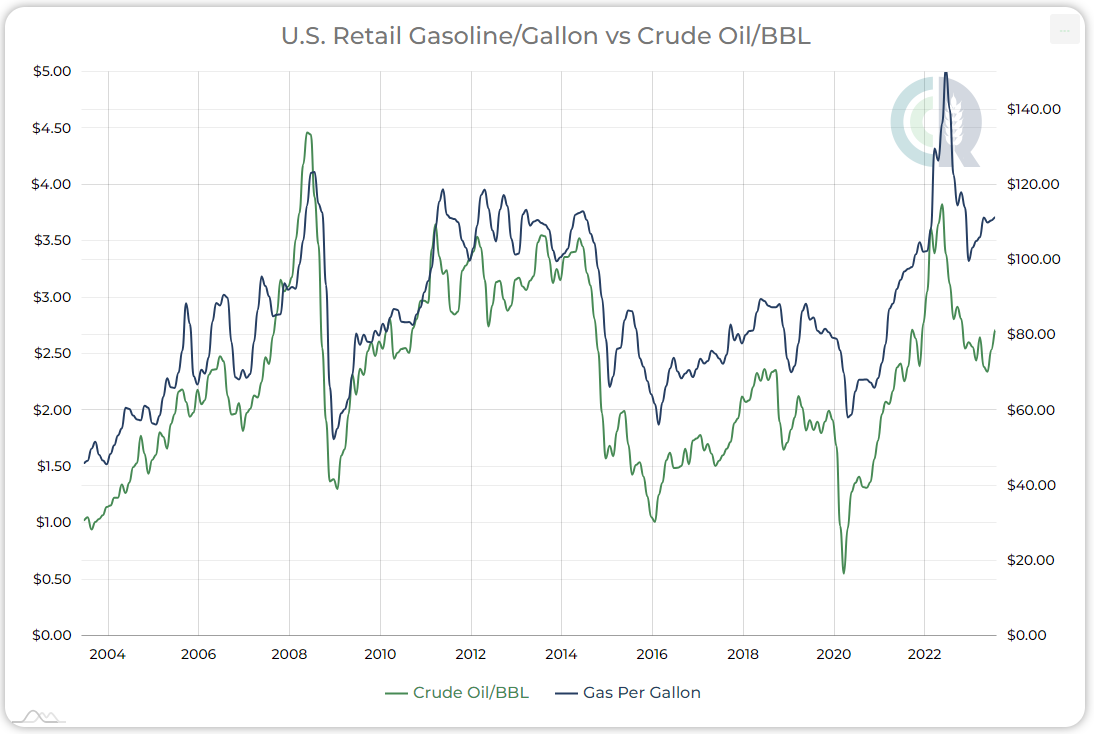

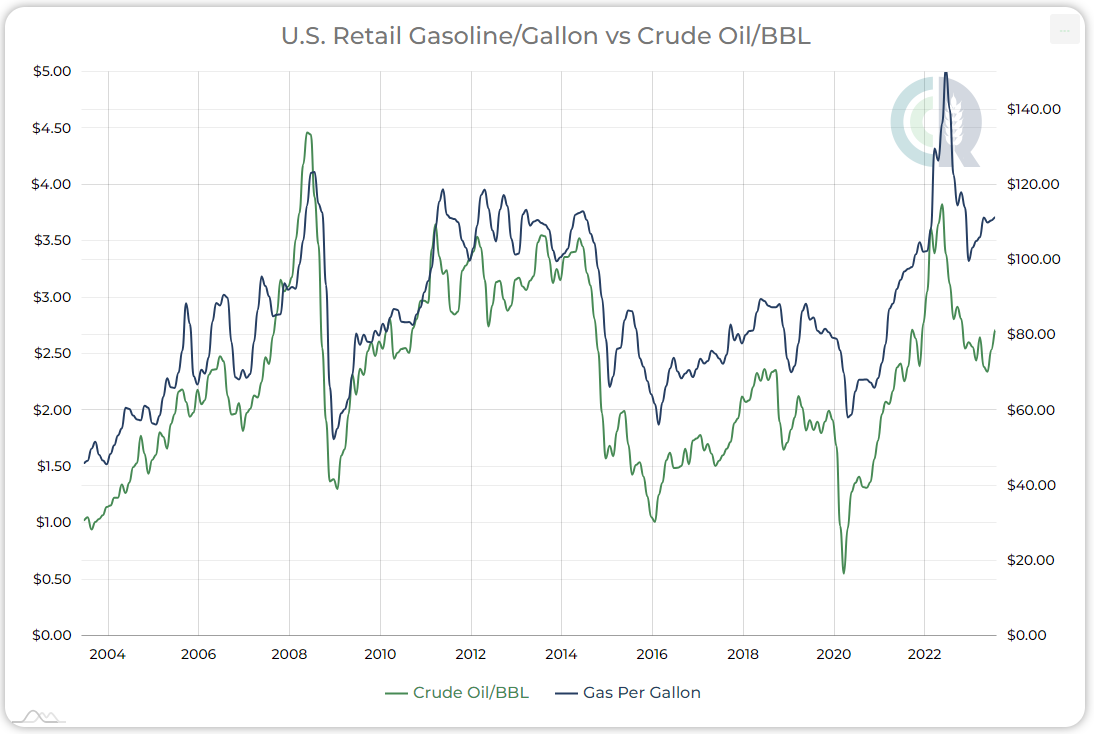

Gasoline prices and crude oil prices are highly correlated, as one product is derived from the other, but there are additional variables in the equation that investors may have overlooked.

With the retail price of gasoline once again nearing $4 per gallon, one might presume that a barrel of oil is trading well over $100. While crude oil futures have recently broken out of their range to a new 2023 high, they remain comfortably below the century mark at $90 per barrel.

Why is there seemingly such a disconnect between crude oil prices on the global market and the price of gasoline at your local service station? Drivers tend to follow crude oil prices and use them as a proxy for gasoline prices, with an understanding of the price relationship based on past experience. For the domestic benchmark West Texas Intermediate (WTI), $100 per barrel is a nice round figure which signifies a high price and serves as a topic of discussion.

In the past, the price of gasoline was basically a function of the price of oil because acquiring crude was the choke point in the chain of production. This relationship has changed in the past 18 months.

- In June of 2008, when WTI reached $140 per barrel, gasoline cost $4.10 per gallon.

- In early 2023, the price of WTI was in the $70 per barrel range while gasoline cost about $3.50.

Differences Between Domestic and International Petroleum Markets

Gasoline has increased in value relative to crude oil, and the reason for this comes down to asymmetric markets and a production bottleneck. Though they are correlated, the supply and demand factors for gasoline are not the same as the supply and demand factors for crude oil. The domestic petroleum market is not the international petroleum market.

In 2020, United States domestic crude oil production fell from a record 13 million barrels per day to less than 10 million due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, it has recovered all the way to 12.8 million barrels per day, only 1.5% below the pre-pandemic high and more than at any time prior to 2019.

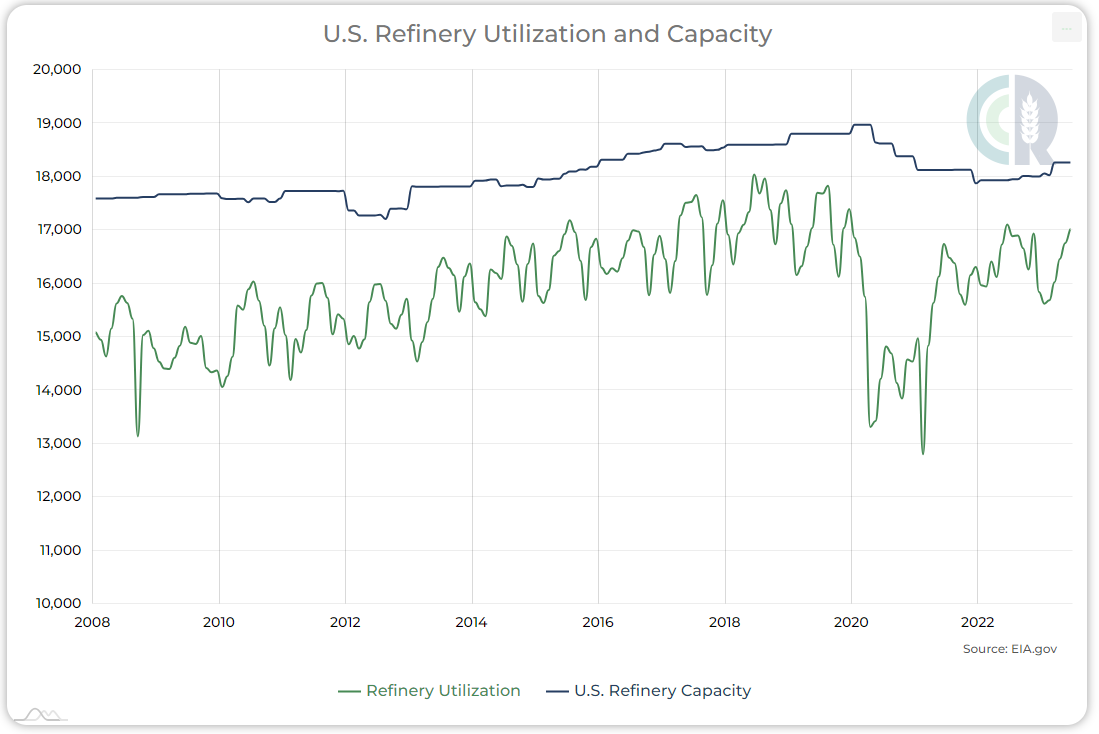

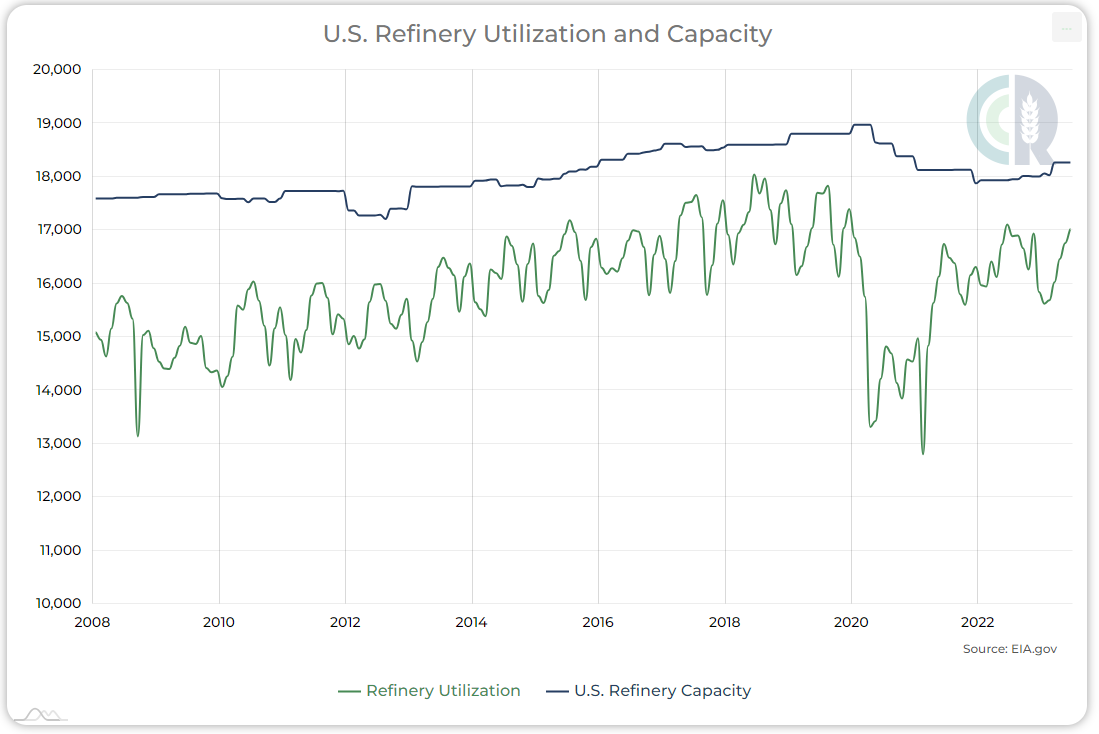

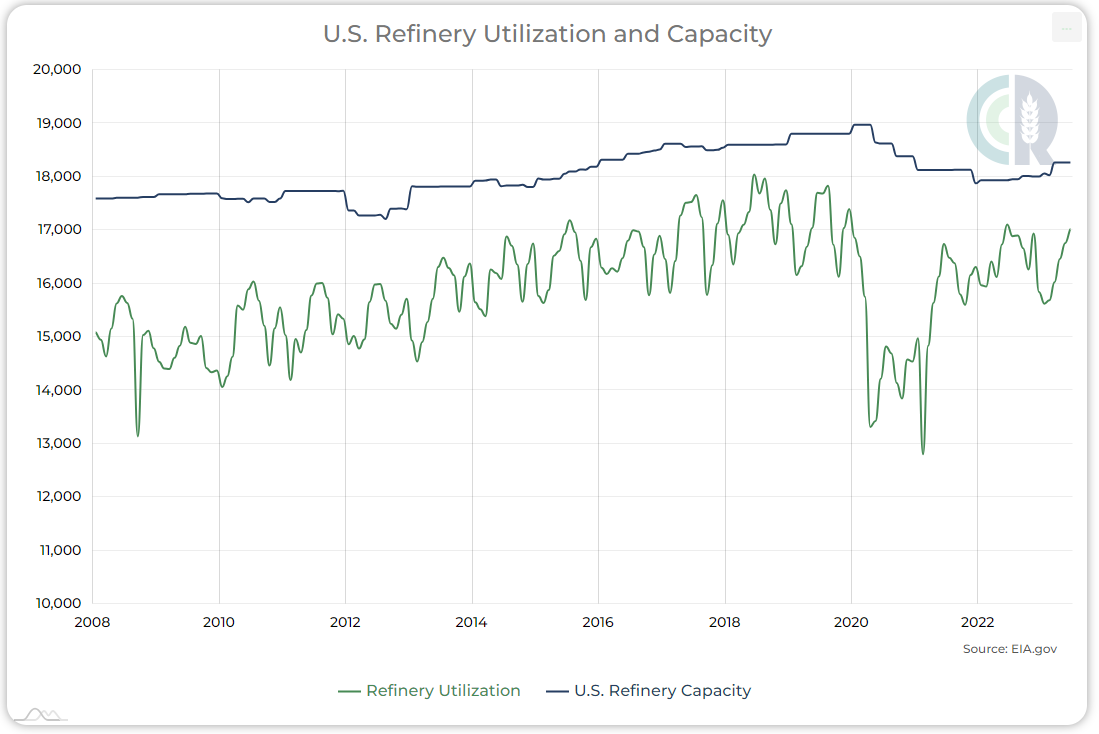

US crude oil distillation (refining) capacity during the same period reached a high of 19 million barrels per day in early 2020 before falling to 17.9 million during the lockdowns. As of June 2023, refining capacity recovered to 18.3 million barrels per day, down 4% from its pre-pandemic record.

A Closer Look at Domestic Oil Production

A 4% drop in refining capacity with only a 1.5% drop in crude production is enough to disrupt the industry, but the difference is even more stark when you compare these figures over a 10-year period. From June 2013 to June 2023, domestic crude oil production grew from 7.3 million barrels per day to 12.3 million barrels per day (a gain of 68%), while refining capacity grew from 17.8 million barrels per day to 18.3 million barrels per day (only a 2.8% increase).

The gains in domestic oil production in recent years have been offset by a decrease in net imports. The U.S. has become a net exporter of crude, indicating that a shortage of oil is not the heart of the issue. For that, we should look at refining capacity versus consumption.

Beyond the seasonal variations that can be seen each year, there was a clear upward trend of refinery utilization approaching relatively unchanged refining capacity. Production has still not fully recovered from the drop caused by the pandemic.

US domestic petroleum consumption has grown from 19 million barrels per day to 20.5 million barrels per day over the past 10 years at a very consistent pace (with the exception of a drop in 2020). That doesn’t seem like a dramatic increase, but it is up 7.8% compared with 4% growth in refining capacity. That difference of 3.8% is responsible for a major boost to the crack spread.

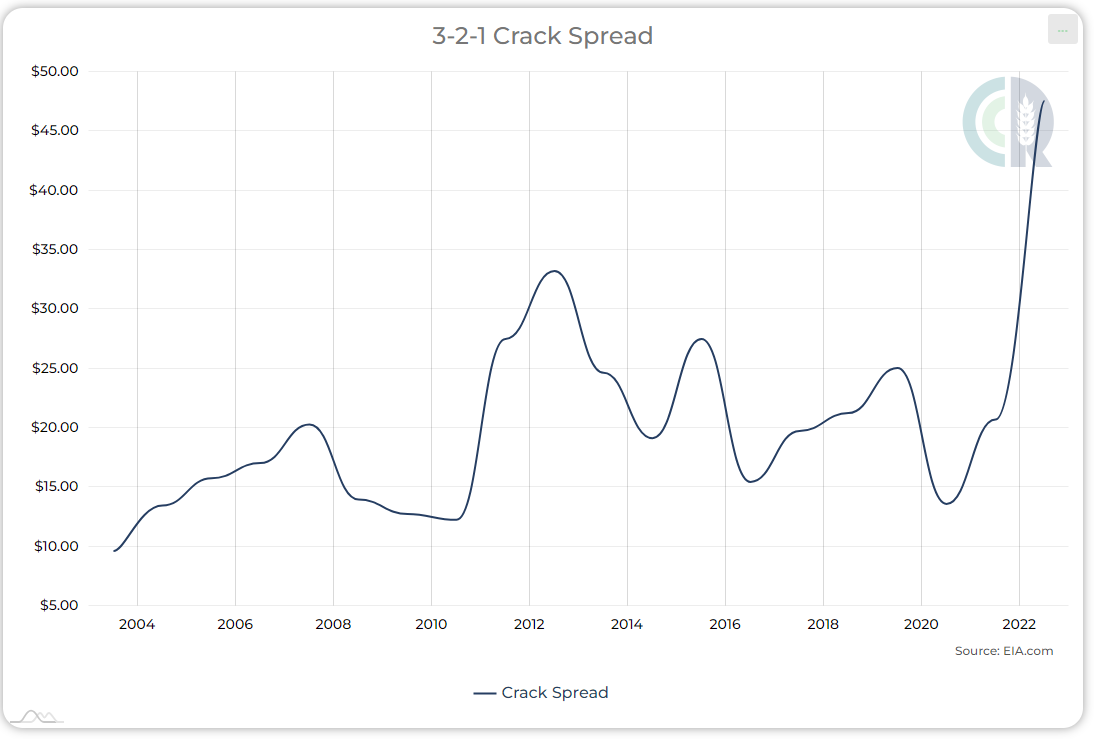

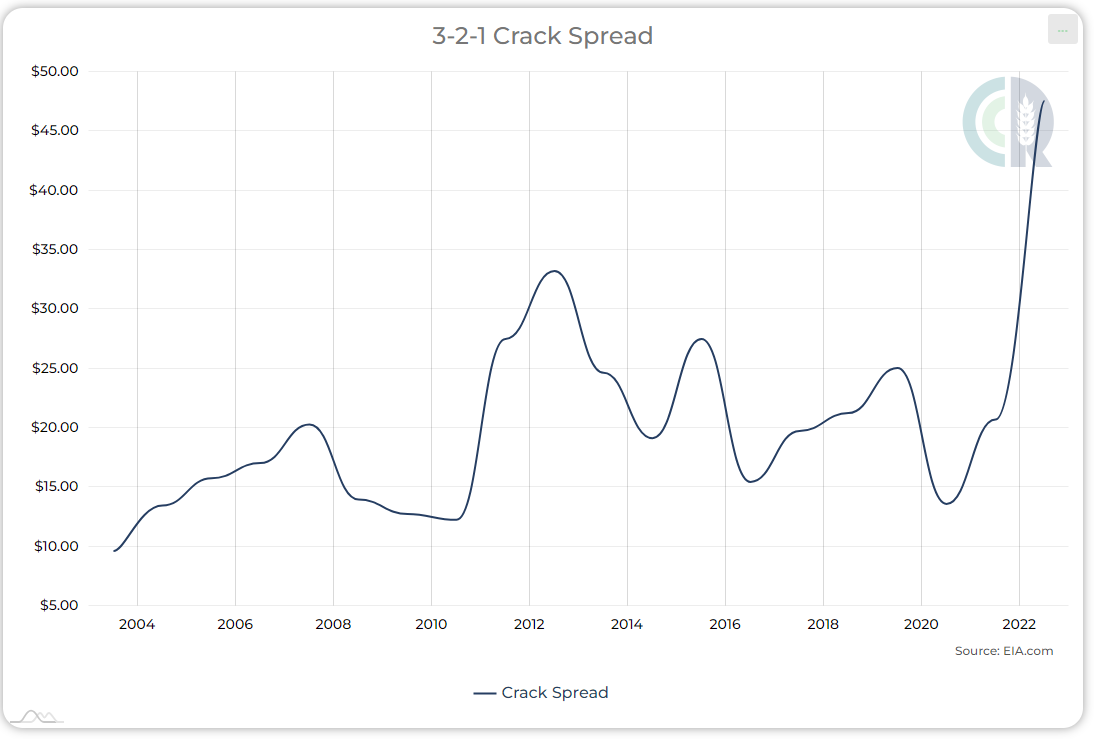

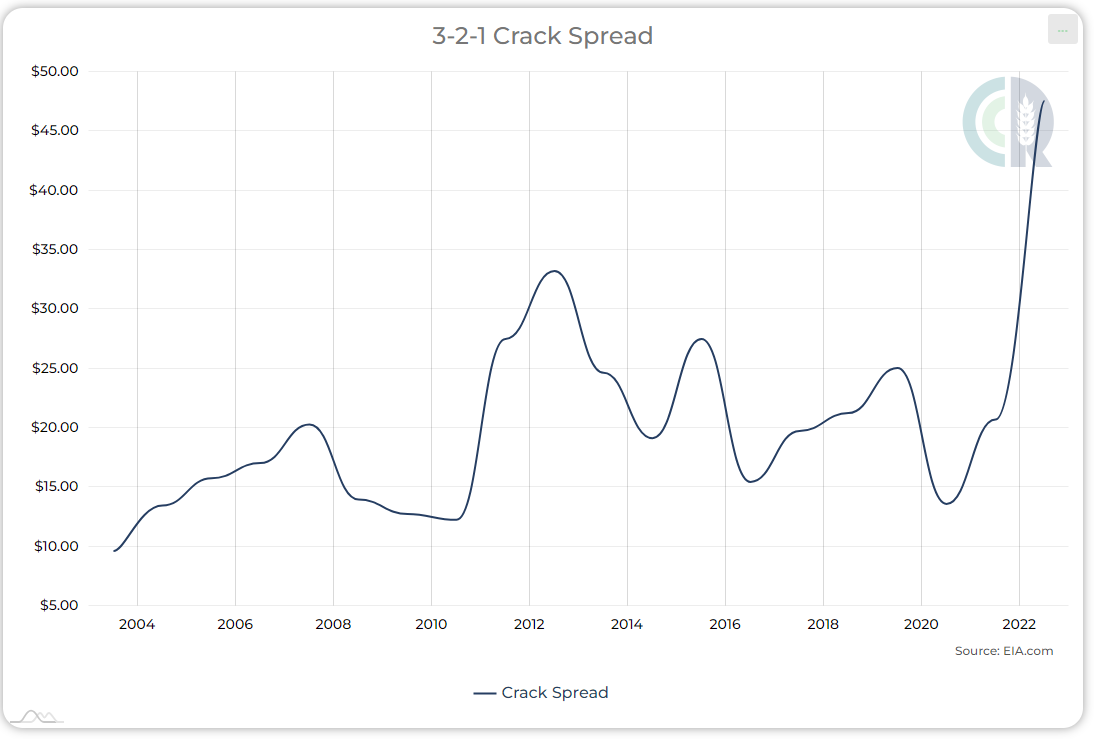

The crack spread is the difference between the price of a barrel of oil and the value of its distillates (refined products), which is essentially the oil refinery’s gross profit margin. Historically, prior to the year 2000, the average crack spread was about $10. It would fluctuate based on market conditions but was not particularly volatile.

The 3:2:1 crack spread approximates the product yield at a typical U.S. refinery: for every three barrels of crude oil the refinery processes, it makes two barrels of gasoline and one barrel of distillate fuel.

In the 2000s and 2010s, the crack spread began to range between $10 and $20. It occasionally spiked above $30 for short periods, typically following a big move in the price of oil. Beginning in February 2022, the crack spread began a relentless push higher to a record peak above $50. It has since consistently remained in the $30s and $40s. This means that every barrel of oil that a refiner bought for $80 this year was distilled into more than $110 worth of petroleum products. How did it grow to that point?

Factors Impacting Refining Capacity in the U.S.

There has not been a high-capacity refinery (over 50,000 barrels per day) built in the United States since 1977. The shortage has been exacerbated by recent fires at two of the nation’s largest refineries in Galveston, Texas and Garyville, La. Those facilities have a capacity of nearly 600,000 barrels per day each.

The tremendous amount of capital and time required to build a refinery, combined with the uncertain long-term future of the fossil fuel industry, has dissuaded companies from building new refineries in recent decades. However, a gross profit margin of 40% is bound to spark some interest.

Southern Rock Energy Partners is spending $5.6 billion on a new refinery scheduled to open in Oklahoma in 2027, capable of producing 250,000 barrels per day. It will be the first major refinery built in 50 years, and possibly a sign of things to come. That is still four years away from opening, and not large enough to have a major impact.

The domestic refinery shortage is only part of the issue driving up gas prices. The refining capacity in most other countries is even worse. As a result, there is greater demand and a higher market price for refined products overseas. This means that even if the U.S. built more than enough refining capacity for its own needs, there would still be a global shortage of refined products, encouraging more exports and keeping domestic gasoline prices somewhat elevated.

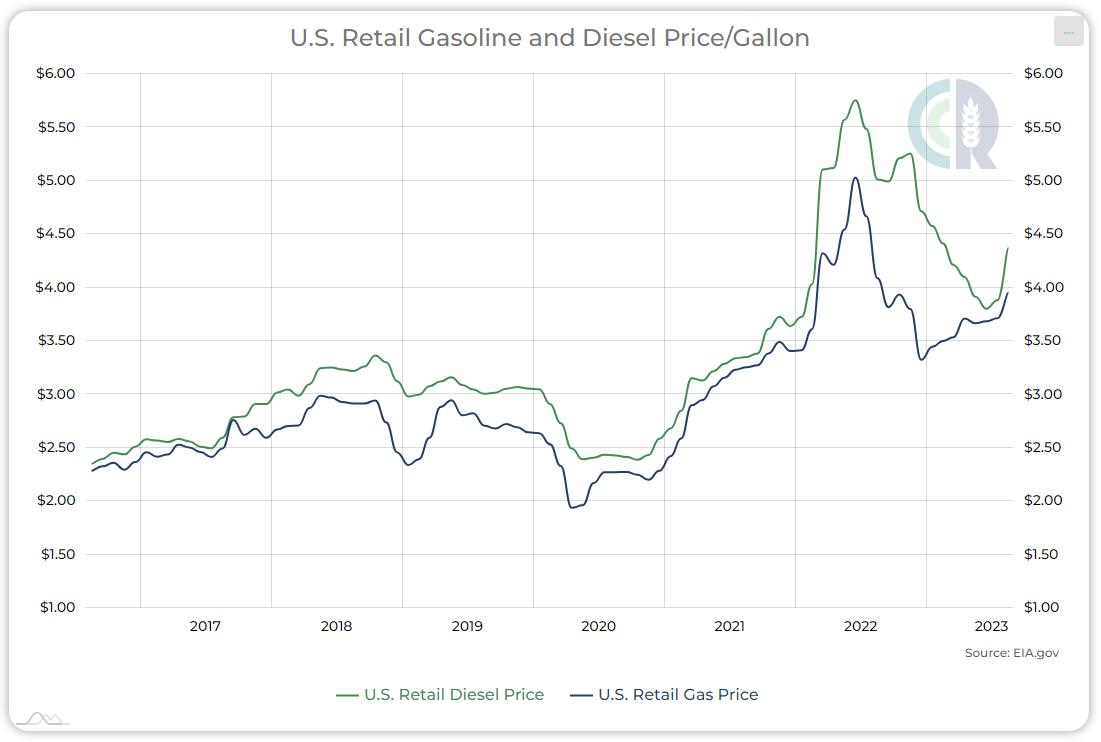

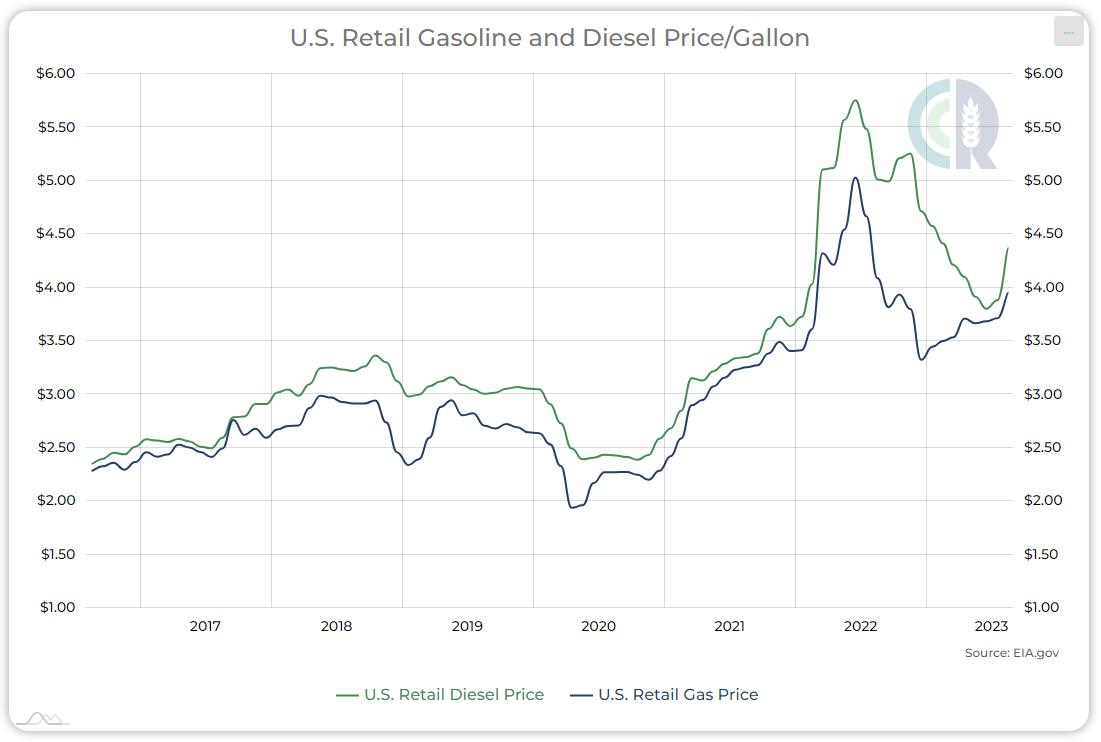

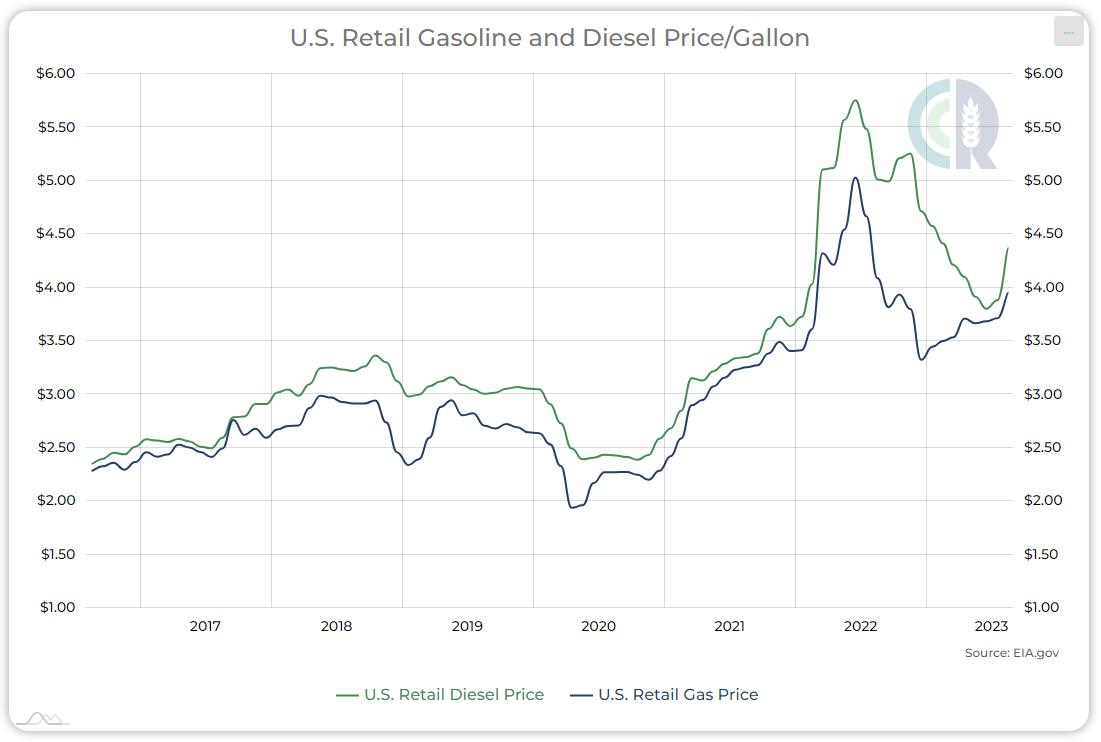

We see the effect of demand for refined products in the comparison of diesel and regular unleaded gasoline. Diesel is the standard in Europe, which relies almost entirely on imported crude and is more heavily impacted by changes in the global market.

Just a few years ago, diesel and regular gasoline were essentially the same price. Since early 2022, that spread has grown to well over one dollar at times.

Not surprisingly, the nations that have increased their refining capacity most dramatically in the last ten years are China, Russia, and India. While discussions of a BRICS currency have been overly optimistic, there is no doubt that this alliance is seeking energy independence. In the short run that will be extremely difficult to accomplish, but they seem to be playing the long game.

OPEC+ nations see the growing crack spread as siphoning off their own profits. Saudi Arabia will not continue selling oil for less than $100 if American consumers are paying over $4 for gasoline. This is why they’ve reduced output.

Conclusion and Outlook

It is often the overlooked aspects of commodity markets that cause interesting price dynamics, not the factors everyone had expected. Considering all the concerns within the energy sector in recent years about peak oil, Middle East conflict, sanctions against Russia, climate change regulations destroying the fossil fuel industry, or electric vehicles killing demand for the internal combustion engine; we ended up with a completely different problem.

The US economy has all the oil it needs but cannot seem to convert it into gasoline and diesel at a fast enough rate, because those fuel sources are still very much in high demand. Rather than crude oil pushing up the price of gasoline, we have gasoline pulling up the price of oil.

With an election just over one year out, incumbent politicians will be looking for ways to lower gas prices. That will be a difficult task because it seems the only way energy prices will fall substantially in the next year would be if the economy enters a recession, which would also not be good for reelection chances. They are between a rock and a hard place.

With few other options available, watch for the current administration to restrict the exportation of refined petroleum products in an effort to lower gasoline prices at home. Will that work? Perhaps in the short run.

We’ve already seen a Republican primary debate where candidates spoke about increasing the number of oil drilling sites in the United States. It’s not a great political talking point, as by November 2024 the US will likely be producing record amounts of crude. As usual, both parties are getting it wrong.

Unless the U.S. dramatically increases refining capacity, all the oil in the world isn’t going to bring gasoline back to $2 per gallon. Instead of “Drill, baby, drill,” voters in this election cycle should be chanting “Refine, baby, refine!”

Watch for the crack spread to remain volatile for at least the next 14 months, and likely beyond. Rather than trading the spread outright, we recommend using it as an informational tool to help choose entry and exit points. If you want to go long crude oil, do it when the crack spread is at its widest (as it was last month, August 2023). If you want to go long on gasoline, wait until after the spread has narrowed.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Cracking the Gasoline Market

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform

Gasoline prices and crude oil prices are highly correlated, as one product is derived from the other, but there are additional variables in the equation that investors may have overlooked.

With the retail price of gasoline once again nearing $4 per gallon, one might presume that a barrel of oil is trading well over $100. While crude oil futures have recently broken out of their range to a new 2023 high, they remain comfortably below the century mark at $90 per barrel.

Why is there seemingly such a disconnect between crude oil prices on the global market and the price of gasoline at your local service station? Drivers tend to follow crude oil prices and use them as a proxy for gasoline prices, with an understanding of the price relationship based on past experience. For the domestic benchmark West Texas Intermediate (WTI), $100 per barrel is a nice round figure which signifies a high price and serves as a topic of discussion.

In the past, the price of gasoline was basically a function of the price of oil because acquiring crude was the choke point in the chain of production. This relationship has changed in the past 18 months.

- In June of 2008, when WTI reached $140 per barrel, gasoline cost $4.10 per gallon.

- In early 2023, the price of WTI was in the $70 per barrel range while gasoline cost about $3.50.

Differences Between Domestic and International Petroleum Markets

Gasoline has increased in value relative to crude oil, and the reason for this comes down to asymmetric markets and a production bottleneck. Though they are correlated, the supply and demand factors for gasoline are not the same as the supply and demand factors for crude oil. The domestic petroleum market is not the international petroleum market.

In 2020, United States domestic crude oil production fell from a record 13 million barrels per day to less than 10 million due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, it has recovered all the way to 12.8 million barrels per day, only 1.5% below the pre-pandemic high and more than at any time prior to 2019.

US crude oil distillation (refining) capacity during the same period reached a high of 19 million barrels per day in early 2020 before falling to 17.9 million during the lockdowns. As of June 2023, refining capacity recovered to 18.3 million barrels per day, down 4% from its pre-pandemic record.

A Closer Look at Domestic Oil Production

A 4% drop in refining capacity with only a 1.5% drop in crude production is enough to disrupt the industry, but the difference is even more stark when you compare these figures over a 10-year period. From June 2013 to June 2023, domestic crude oil production grew from 7.3 million barrels per day to 12.3 million barrels per day (a gain of 68%), while refining capacity grew from 17.8 million barrels per day to 18.3 million barrels per day (only a 2.8% increase).

The gains in domestic oil production in recent years have been offset by a decrease in net imports. The U.S. has become a net exporter of crude, indicating that a shortage of oil is not the heart of the issue. For that, we should look at refining capacity versus consumption.

Beyond the seasonal variations that can be seen each year, there was a clear upward trend of refinery utilization approaching relatively unchanged refining capacity. Production has still not fully recovered from the drop caused by the pandemic.

US domestic petroleum consumption has grown from 19 million barrels per day to 20.5 million barrels per day over the past 10 years at a very consistent pace (with the exception of a drop in 2020). That doesn’t seem like a dramatic increase, but it is up 7.8% compared with 4% growth in refining capacity. That difference of 3.8% is responsible for a major boost to the crack spread.

The crack spread is the difference between the price of a barrel of oil and the value of its distillates (refined products), which is essentially the oil refinery’s gross profit margin. Historically, prior to the year 2000, the average crack spread was about $10. It would fluctuate based on market conditions but was not particularly volatile.

The 3:2:1 crack spread approximates the product yield at a typical U.S. refinery: for every three barrels of crude oil the refinery processes, it makes two barrels of gasoline and one barrel of distillate fuel.

In the 2000s and 2010s, the crack spread began to range between $10 and $20. It occasionally spiked above $30 for short periods, typically following a big move in the price of oil. Beginning in February 2022, the crack spread began a relentless push higher to a record peak above $50. It has since consistently remained in the $30s and $40s. This means that every barrel of oil that a refiner bought for $80 this year was distilled into more than $110 worth of petroleum products. How did it grow to that point?

Factors Impacting Refining Capacity in the U.S.

There has not been a high-capacity refinery (over 50,000 barrels per day) built in the United States since 1977. The shortage has been exacerbated by recent fires at two of the nation’s largest refineries in Galveston, Texas and Garyville, La. Those facilities have a capacity of nearly 600,000 barrels per day each.

The tremendous amount of capital and time required to build a refinery, combined with the uncertain long-term future of the fossil fuel industry, has dissuaded companies from building new refineries in recent decades. However, a gross profit margin of 40% is bound to spark some interest.

Southern Rock Energy Partners is spending $5.6 billion on a new refinery scheduled to open in Oklahoma in 2027, capable of producing 250,000 barrels per day. It will be the first major refinery built in 50 years, and possibly a sign of things to come. That is still four years away from opening, and not large enough to have a major impact.

The domestic refinery shortage is only part of the issue driving up gas prices. The refining capacity in most other countries is even worse. As a result, there is greater demand and a higher market price for refined products overseas. This means that even if the U.S. built more than enough refining capacity for its own needs, there would still be a global shortage of refined products, encouraging more exports and keeping domestic gasoline prices somewhat elevated.

We see the effect of demand for refined products in the comparison of diesel and regular unleaded gasoline. Diesel is the standard in Europe, which relies almost entirely on imported crude and is more heavily impacted by changes in the global market.

Just a few years ago, diesel and regular gasoline were essentially the same price. Since early 2022, that spread has grown to well over one dollar at times.

Not surprisingly, the nations that have increased their refining capacity most dramatically in the last ten years are China, Russia, and India. While discussions of a BRICS currency have been overly optimistic, there is no doubt that this alliance is seeking energy independence. In the short run that will be extremely difficult to accomplish, but they seem to be playing the long game.

OPEC+ nations see the growing crack spread as siphoning off their own profits. Saudi Arabia will not continue selling oil for less than $100 if American consumers are paying over $4 for gasoline. This is why they’ve reduced output.

Conclusion and Outlook

It is often the overlooked aspects of commodity markets that cause interesting price dynamics, not the factors everyone had expected. Considering all the concerns within the energy sector in recent years about peak oil, Middle East conflict, sanctions against Russia, climate change regulations destroying the fossil fuel industry, or electric vehicles killing demand for the internal combustion engine; we ended up with a completely different problem.

The US economy has all the oil it needs but cannot seem to convert it into gasoline and diesel at a fast enough rate, because those fuel sources are still very much in high demand. Rather than crude oil pushing up the price of gasoline, we have gasoline pulling up the price of oil.

With an election just over one year out, incumbent politicians will be looking for ways to lower gas prices. That will be a difficult task because it seems the only way energy prices will fall substantially in the next year would be if the economy enters a recession, which would also not be good for reelection chances. They are between a rock and a hard place.

With few other options available, watch for the current administration to restrict the exportation of refined petroleum products in an effort to lower gasoline prices at home. Will that work? Perhaps in the short run.

We’ve already seen a Republican primary debate where candidates spoke about increasing the number of oil drilling sites in the United States. It’s not a great political talking point, as by November 2024 the US will likely be producing record amounts of crude. As usual, both parties are getting it wrong.

Unless the U.S. dramatically increases refining capacity, all the oil in the world isn’t going to bring gasoline back to $2 per gallon. Instead of “Drill, baby, drill,” voters in this election cycle should be chanting “Refine, baby, refine!”

Watch for the crack spread to remain volatile for at least the next 14 months, and likely beyond. Rather than trading the spread outright, we recommend using it as an informational tool to help choose entry and exit points. If you want to go long crude oil, do it when the crack spread is at its widest (as it was last month, August 2023). If you want to go long on gasoline, wait until after the spread has narrowed.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Cracking the Gasoline Market

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform

Gasoline prices and crude oil prices are highly correlated, as one product is derived from the other, but there are additional variables in the equation that investors may have overlooked.

With the retail price of gasoline once again nearing $4 per gallon, one might presume that a barrel of oil is trading well over $100. While crude oil futures have recently broken out of their range to a new 2023 high, they remain comfortably below the century mark at $90 per barrel.

Why is there seemingly such a disconnect between crude oil prices on the global market and the price of gasoline at your local service station? Drivers tend to follow crude oil prices and use them as a proxy for gasoline prices, with an understanding of the price relationship based on past experience. For the domestic benchmark West Texas Intermediate (WTI), $100 per barrel is a nice round figure which signifies a high price and serves as a topic of discussion.

In the past, the price of gasoline was basically a function of the price of oil because acquiring crude was the choke point in the chain of production. This relationship has changed in the past 18 months.

- In June of 2008, when WTI reached $140 per barrel, gasoline cost $4.10 per gallon.

- In early 2023, the price of WTI was in the $70 per barrel range while gasoline cost about $3.50.

Differences Between Domestic and International Petroleum Markets

Gasoline has increased in value relative to crude oil, and the reason for this comes down to asymmetric markets and a production bottleneck. Though they are correlated, the supply and demand factors for gasoline are not the same as the supply and demand factors for crude oil. The domestic petroleum market is not the international petroleum market.

In 2020, United States domestic crude oil production fell from a record 13 million barrels per day to less than 10 million due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, it has recovered all the way to 12.8 million barrels per day, only 1.5% below the pre-pandemic high and more than at any time prior to 2019.

US crude oil distillation (refining) capacity during the same period reached a high of 19 million barrels per day in early 2020 before falling to 17.9 million during the lockdowns. As of June 2023, refining capacity recovered to 18.3 million barrels per day, down 4% from its pre-pandemic record.

A Closer Look at Domestic Oil Production

A 4% drop in refining capacity with only a 1.5% drop in crude production is enough to disrupt the industry, but the difference is even more stark when you compare these figures over a 10-year period. From June 2013 to June 2023, domestic crude oil production grew from 7.3 million barrels per day to 12.3 million barrels per day (a gain of 68%), while refining capacity grew from 17.8 million barrels per day to 18.3 million barrels per day (only a 2.8% increase).

The gains in domestic oil production in recent years have been offset by a decrease in net imports. The U.S. has become a net exporter of crude, indicating that a shortage of oil is not the heart of the issue. For that, we should look at refining capacity versus consumption.

Beyond the seasonal variations that can be seen each year, there was a clear upward trend of refinery utilization approaching relatively unchanged refining capacity. Production has still not fully recovered from the drop caused by the pandemic.

US domestic petroleum consumption has grown from 19 million barrels per day to 20.5 million barrels per day over the past 10 years at a very consistent pace (with the exception of a drop in 2020). That doesn’t seem like a dramatic increase, but it is up 7.8% compared with 4% growth in refining capacity. That difference of 3.8% is responsible for a major boost to the crack spread.

The crack spread is the difference between the price of a barrel of oil and the value of its distillates (refined products), which is essentially the oil refinery’s gross profit margin. Historically, prior to the year 2000, the average crack spread was about $10. It would fluctuate based on market conditions but was not particularly volatile.

The 3:2:1 crack spread approximates the product yield at a typical U.S. refinery: for every three barrels of crude oil the refinery processes, it makes two barrels of gasoline and one barrel of distillate fuel.

In the 2000s and 2010s, the crack spread began to range between $10 and $20. It occasionally spiked above $30 for short periods, typically following a big move in the price of oil. Beginning in February 2022, the crack spread began a relentless push higher to a record peak above $50. It has since consistently remained in the $30s and $40s. This means that every barrel of oil that a refiner bought for $80 this year was distilled into more than $110 worth of petroleum products. How did it grow to that point?

Factors Impacting Refining Capacity in the U.S.

There has not been a high-capacity refinery (over 50,000 barrels per day) built in the United States since 1977. The shortage has been exacerbated by recent fires at two of the nation’s largest refineries in Galveston, Texas and Garyville, La. Those facilities have a capacity of nearly 600,000 barrels per day each.

The tremendous amount of capital and time required to build a refinery, combined with the uncertain long-term future of the fossil fuel industry, has dissuaded companies from building new refineries in recent decades. However, a gross profit margin of 40% is bound to spark some interest.

Southern Rock Energy Partners is spending $5.6 billion on a new refinery scheduled to open in Oklahoma in 2027, capable of producing 250,000 barrels per day. It will be the first major refinery built in 50 years, and possibly a sign of things to come. That is still four years away from opening, and not large enough to have a major impact.

The domestic refinery shortage is only part of the issue driving up gas prices. The refining capacity in most other countries is even worse. As a result, there is greater demand and a higher market price for refined products overseas. This means that even if the U.S. built more than enough refining capacity for its own needs, there would still be a global shortage of refined products, encouraging more exports and keeping domestic gasoline prices somewhat elevated.

We see the effect of demand for refined products in the comparison of diesel and regular unleaded gasoline. Diesel is the standard in Europe, which relies almost entirely on imported crude and is more heavily impacted by changes in the global market.

Just a few years ago, diesel and regular gasoline were essentially the same price. Since early 2022, that spread has grown to well over one dollar at times.

Not surprisingly, the nations that have increased their refining capacity most dramatically in the last ten years are China, Russia, and India. While discussions of a BRICS currency have been overly optimistic, there is no doubt that this alliance is seeking energy independence. In the short run that will be extremely difficult to accomplish, but they seem to be playing the long game.

OPEC+ nations see the growing crack spread as siphoning off their own profits. Saudi Arabia will not continue selling oil for less than $100 if American consumers are paying over $4 for gasoline. This is why they’ve reduced output.

Conclusion and Outlook

It is often the overlooked aspects of commodity markets that cause interesting price dynamics, not the factors everyone had expected. Considering all the concerns within the energy sector in recent years about peak oil, Middle East conflict, sanctions against Russia, climate change regulations destroying the fossil fuel industry, or electric vehicles killing demand for the internal combustion engine; we ended up with a completely different problem.

The US economy has all the oil it needs but cannot seem to convert it into gasoline and diesel at a fast enough rate, because those fuel sources are still very much in high demand. Rather than crude oil pushing up the price of gasoline, we have gasoline pulling up the price of oil.

With an election just over one year out, incumbent politicians will be looking for ways to lower gas prices. That will be a difficult task because it seems the only way energy prices will fall substantially in the next year would be if the economy enters a recession, which would also not be good for reelection chances. They are between a rock and a hard place.

With few other options available, watch for the current administration to restrict the exportation of refined petroleum products in an effort to lower gasoline prices at home. Will that work? Perhaps in the short run.

We’ve already seen a Republican primary debate where candidates spoke about increasing the number of oil drilling sites in the United States. It’s not a great political talking point, as by November 2024 the US will likely be producing record amounts of crude. As usual, both parties are getting it wrong.

Unless the U.S. dramatically increases refining capacity, all the oil in the world isn’t going to bring gasoline back to $2 per gallon. Instead of “Drill, baby, drill,” voters in this election cycle should be chanting “Refine, baby, refine!”

Watch for the crack spread to remain volatile for at least the next 14 months, and likely beyond. Rather than trading the spread outright, we recommend using it as an informational tool to help choose entry and exit points. If you want to go long crude oil, do it when the crack spread is at its widest (as it was last month, August 2023). If you want to go long on gasoline, wait until after the spread has narrowed.